The War That Started With a Potato: The Bizarre Tale of the 1859 Pig War

History is often defined by grand ideological clashes, territorial conquests, and the whims of powerful monarchs. But sometimes, history hinges on a hungry farm animal and a patch of potatoes. In 1859, on a small, windswept island in the Pacific Northwest, two of the world’s greatest superpowers—the United States and the British Empire—nearly plunged into a catastrophic war because an American farmer shot a British pig. This is the story of the Pig War, perhaps the most absurd standoff of the 19th century, where cooler heads prevailed just before the cannons could fire.

To understand how a barnyard animal could spark an international crisis, one must look at the geography of the era. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 was supposed to settle the border between American and British possessions in the Pacific Northwest. The treaty stated that the boundary should run through the middle of the channel separating the continent from Vancouver Island. The problem was that there were two channels—Haro Strait and Rosario Strait—with the San Juan Islands sitting squarely between them. Both nations claimed the islands. By 1859, the British Hudson’s Bay Company had established a sheep ranch on San Juan Island, while American settlers had also begun staking claims on the same land.

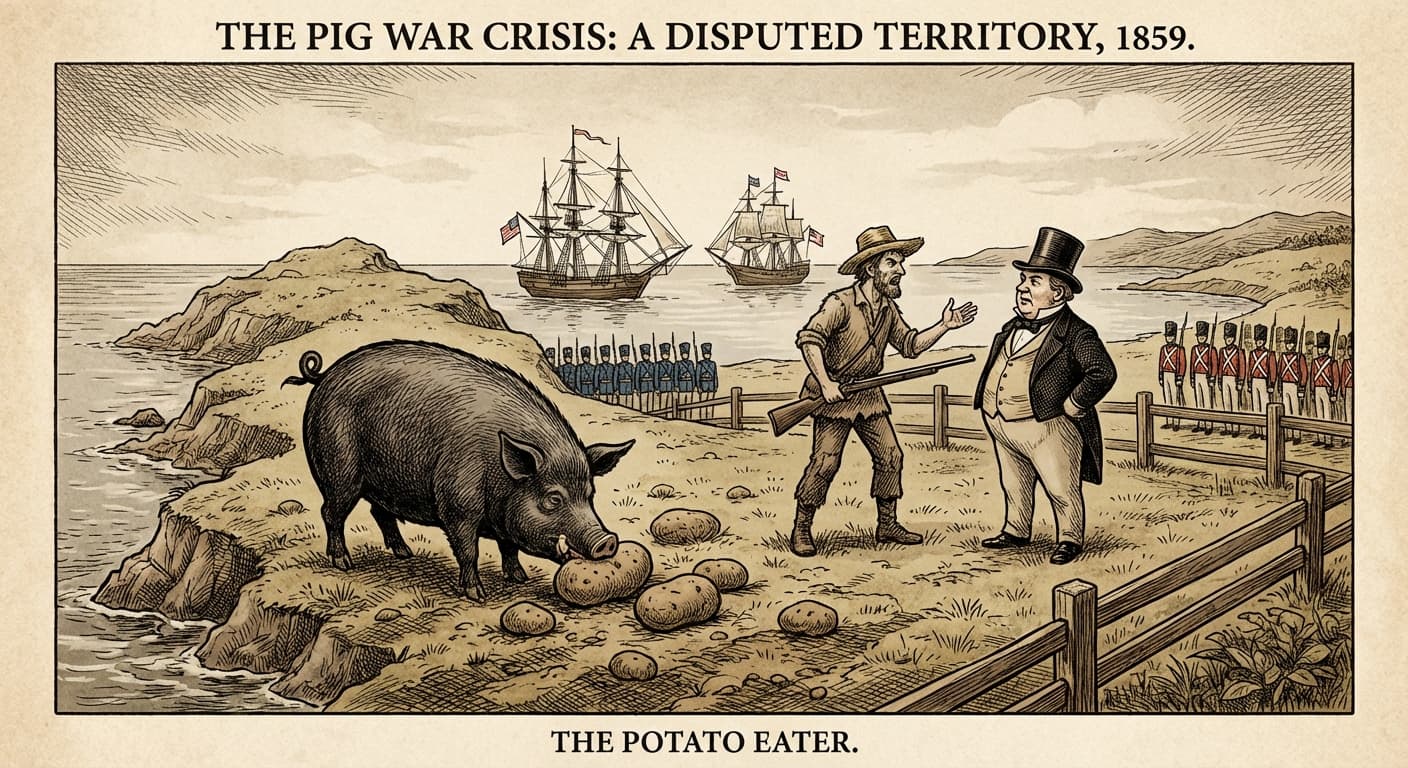

The spark occurred on June 15, 1859. Lyman Cutlar, an American farmer, walked out to his garden to find a large black pig rooting up his potatoes. This was not the first time the animal had raided his crops. Frustrated and defending his livelihood, Cutlar raised his rifle and shot the pig dead. The pig, it turned out, belonged to Charles Griffin, an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company who ran the sheep ranch. Cutlar, a fair-minded man, offered Griffin $10 in compensation. Griffin, incensed by the loss of his prize breeding animal, demanded $100. Cutlar refused to pay the extortionate sum, famously declaring that the pig had been trespassing. Griffin retorted, "It is up to you to keep your potatoes out of my pig."

What should have been a small claims court dispute rapidly spiraled out of control. British authorities threatened to arrest Cutlar. The American settlers, feeling persecuted, called for military protection. Unfortunately for everyone involved, the call was answered by Brigadier General William S. Harney, known as "The Texan Fighter." Harney, a man with a distinct dislike for the British, dispatched the impetuous Captain George Pickett—who would later gain infamy for his disastrous charge at Gettysburg—with 66 soldiers to the island. Pickett declared the island American soil and dared the British to remove him.

The British Governor of Vancouver Island, James Douglas, took the bait. He dispatched three warships under the command of Captain Geoffrey Hornby to dislodge Pickett. The situation escalated with terrifying speed. By August, 461 Americans with 14 cannons were dug in against five British warships mounting 70 guns and carrying over 2,000 experienced Royal Navy sailors and marines. The orders given to the British commanders were to land and engage, but Rear Admiral Robert L. Baynes arrived just in time to assess the situation. Upon seeing the massive buildup of firepower over a minor agricultural dispute, Baynes refused to engage, famously stating that he would not "involve two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig."

News of the standoff finally reached Washington D.C. and London weeks later, shocking leaders on both sides of the Atlantic. President James Buchanan, terrified of a two-front conflict as tensions between the North and South were already boiling over at home, hurriedly sent General Winfield Scott to defuse the situation. Scott, a veteran diplomat and soldier, managed to negotiate a truce. The island would be placed under joint military occupation until a final decision could be made. The British set up camp on the north end of the island, and the Americans on the south.

For the next 12 years, the "war" continued as a remarkably peaceful occupation. The garrisons at English Camp and American Camp became quite friendly. They hosted dinner parties for one another, held athletic competitions, and celebrated each other's holidays. It was said that the British had better booze, while the Americans had better tobacco, leading to a thriving trade between the camps. The dispute was finally resolved in 1872, when Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany, acting as an arbitrator, ruled in favor of the United States, setting the border at the Haro Strait.

Today, the San Juan Island National Historical Park preserves both the American and English camps, flying the Union Jack over the British camp in a rare commemorative gesture. The Pig War remains a unique historical footnote: a conflict that featured warships, future Civil War generals, and imperial posturing, yet resulted in zero human casualties. The only life lost in the entire affair was, unfortunately, the pig.