The Green Wall of the Raj: The Forgotten Story of the Great Hedge of India

When we think of massive, continental barriers constructed to control human movement or trade, the Great Wall of China or the Berlin Wall typically spring to mind. Yet, during the mid-19th century, the British Empire constructed a barrier in India that rivaled the Great Wall in length, yet it has almost entirely vanished from history and the physical landscape. This is the story of the Inland Customs Line, more famously known as the Great Hedge of India—a living wall of thorns that stretched over a thousand miles, designed not to stop an army, but to stop a condiment.

The Salt of the Earth

To understand why anyone would plant a hedge across a subcontinent, one must understand the economics of the British Raj. In the 19th century, salt was not merely a flavor enhancer; it was a biological necessity in India’s searing heat and a crucial preservative for food. Recognizing this inelastic demand, the British East India Company, and later the Crown, imposed a heavy tax on salt.

However, there was a geographic problem. Salt was readily available and cheap in the salt lakes of the west and the coastal regions, but the highest demand was in the populous interior and Bengal. To maintain their monopoly and ensure no one was getting "untaxed" salt, the British needed to hermetically seal off the salt-producing regions from the rest of India. The solution was the Inland Customs Line, a bureaucratic border drawn through the heart of the country.

Botany as a Weapon

Initially, this line was a series of customs posts and dry hedges, but in the 1840s and 1850s, under the administration of Allan Octavian Hume (who, ironically, would later help found the Indian National Congress), the line was fortified into something truly monstrous. Hume realized that dead wood could be burned or carried away, and stone walls were too expensive. The answer was a living barrier.

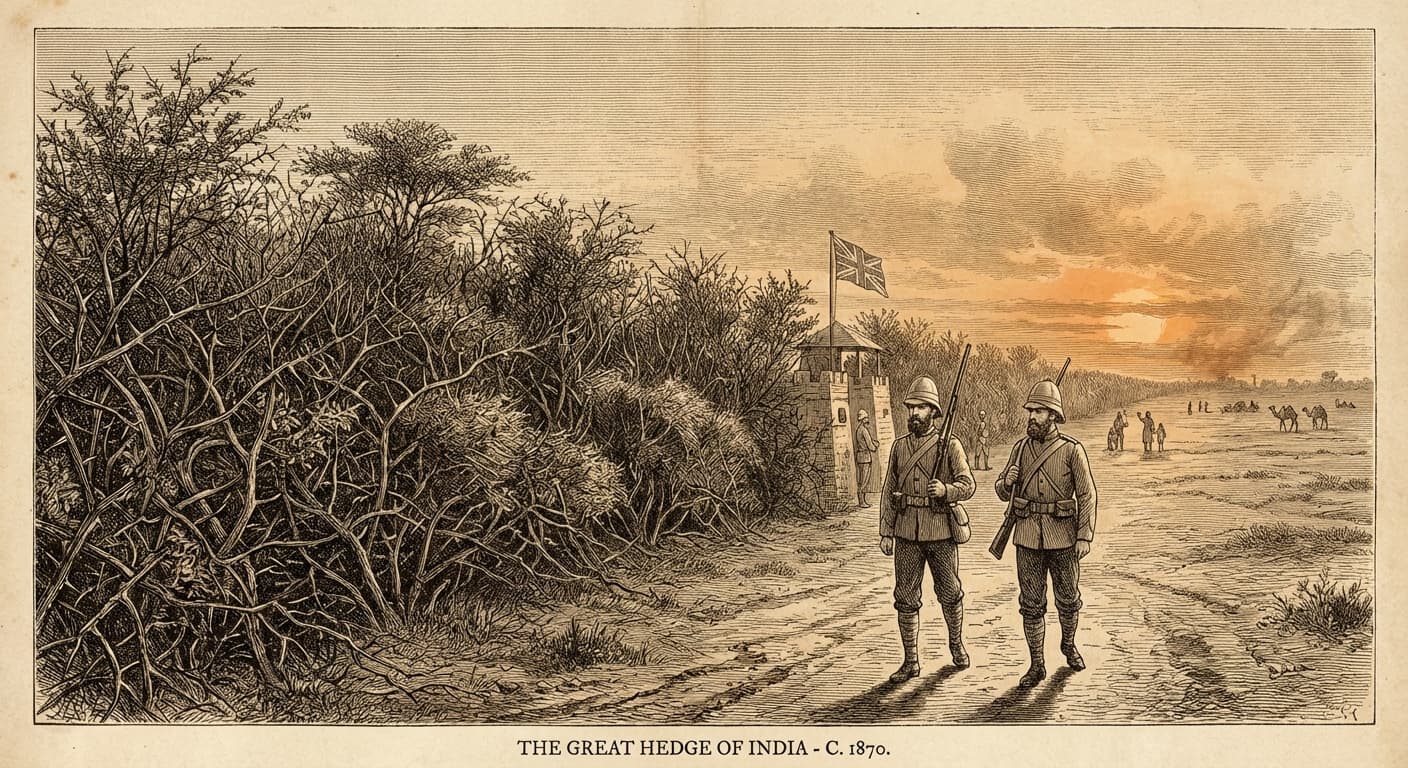

The British began planting a thick, impenetrable thicket of Indian plum, babool, karonda, and euphorbia. This wasn't a garden hedge; it was a bio-engineered fortification. It stood up to twelve feet high and fourteen feet thick. The thorns were long and sharp enough to tear through flesh and clothing, making it impossible for smugglers to carry heavy sacks of salt through the brush.

At its peak in the 1870s, the Inland Customs Line stretched a staggering 2,500 miles—from the foothills of the Himalayas down to Odisha. The "living hedge" portion covered roughly 1,100 miles of this distance. To put that into perspective, the Great Hedge was longer than the distance from London to Rome, maintained meticulously by an army of gardeners and patrolled by 12,000 men.

Life on the Line

The existence of the Hedge created a bizarre micro-society. Customs officers spent their lives patrolling the thorny wall, looking for breaches. Smuggling became a high-stakes game. Desperate locals would try to fling sacks over the hedge, tunnel under it, or bribe the guards. Clashes were common, and the line became a symbol of the Raj's oppressive taxation policies, which often priced salt out of the range of the poorest Indians, leading to salt deprivation and health issues in the interior.

The maintenance required was herculean. The hedge had to be watered, pruned, and protected from locusts, fires, and white ants. It was a masterpiece of colonial administration—a triumph of logistics applied to a morally dubious end.

The Disappearance

So, where is it now? If you visit India today, you will find almost no trace of this botanical behemoth. The end of the Great Hedge came not from a revolution, but from a spreadsheet. By 1879, the British government realized that the cost of maintaining the line and the manpower required to police it was inefficient. They equalized the tax on salt across the country, rendering the internal border obsolete.

Once the order was given to abandon the line, the local population descended upon it. For decades, the hedge had been a barrier; now, it was a source of free firewood in a fuel-scarce land. Within a few years, the Great Hedge was chopped down, burned, and the land reclaimed for agriculture or roads.

For over a century, the Great Hedge of India was forgotten, dismissed as a myth or a minor footnote in administrative logs. It was only in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, thanks largely to the work of historian Roy Moxham, that the scale of this structure was rediscovered. Today, it serves as a fascinating, prickly reminder of the lengths to which empires will go to secure their revenue, illustrating how a structure of immense magnitude can simply vanish when its economic purpose expires.