The Great Moon Hoax of 1835: When Bat-Men Ruled the Headlines

In the sweltering August of 1835, the citizens of New York City were not talking about politics, the economy, or the looming tensions of a growing nation. Instead, they were looking up. Their eyes were fixed on the night sky, their imaginations captivated by a sensational series of articles published in The Sun, a penny newspaper that had just pulled off the greatest media stunt of the 19th century. For one glorious week, the world believed that the moon was teeming with life—specifically, unicorns, bipedal beavers, and winged bat-men.

The Setup: A Telescope to End All Telescopes

The story began on August 25, 1835, with a headline that promised to change human history: "GREAT ASTRONOMICAL DISCOVERIES LATELY MADE BY SIR JOHN HERSCHEL, L.L.D. F.R.S. &c. At the Cape of Good Hope." The article claimed to be reprinted from the Edinburgh Journal of Science (a publication that, unbeknownst to most New Yorkers, had ceased printing years earlier).

According to the report, the famous British astronomer Sir John Herschel had constructed a telescope of such immense magnitude—utilizing an entirely new principle of "hydro-oxygen microscopes"—that it could magnify objects on the lunar surface 42,000 times. The article was laden with dense, pseudo-scientific jargon regarding lenses, focal points, and spectral analysis. To the layperson, it sounded incredibly authoritative; to the scientific community, it was baffling, yet the pedigree of Herschel made it difficult to dismiss outright.

The Lunar Menagerie

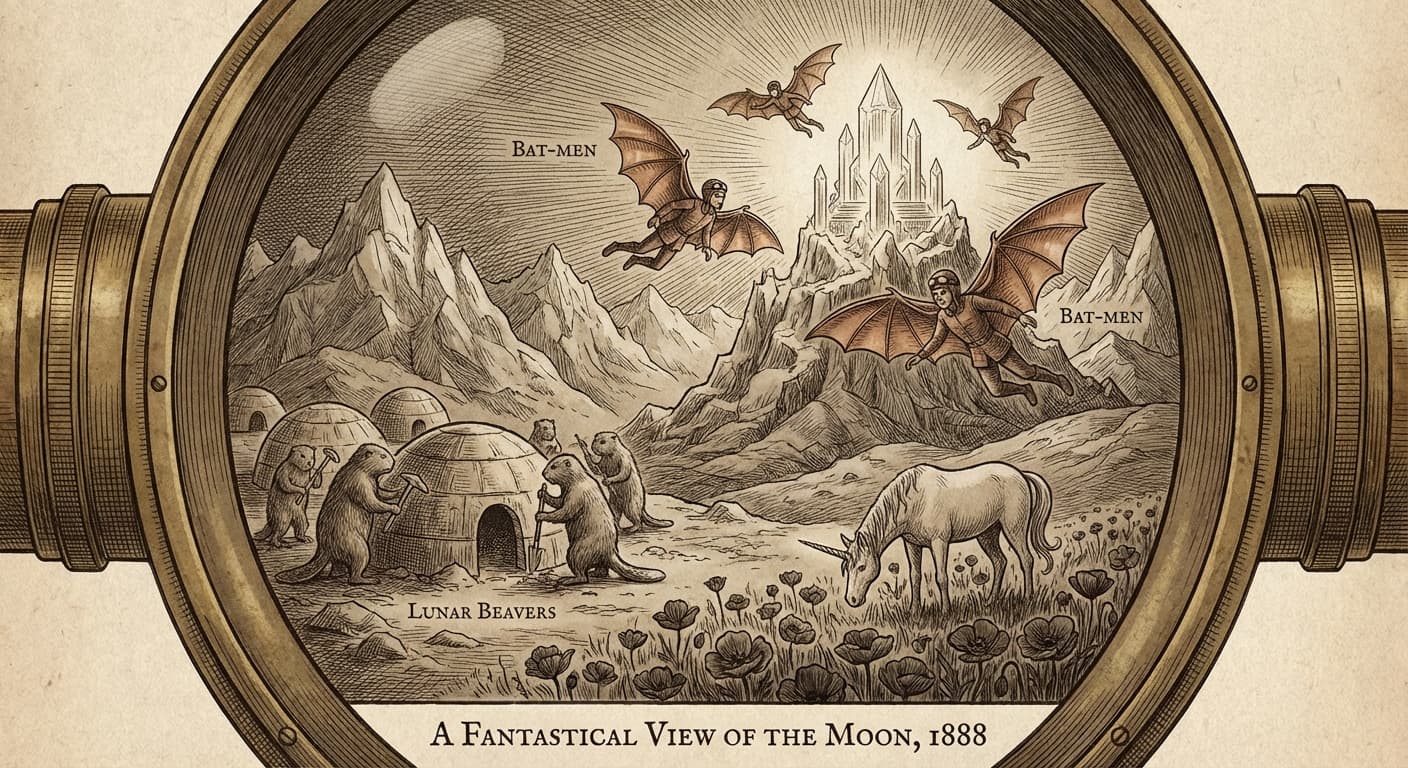

Over the next six days, The Sun released installment after installment, each more fantastic than the last. The initial report described a lunar landscape of basaltic rock and poppy fields. Then came the animals. Readers were introduced to a goat-like creature with a single horn (essentially a unicorn) and spherical amphibians that rolled across the beach.

But the narrative truly took flight—literally—with the introduction of bipedal beavers. These creatures were described as walking on two feet, carrying their young in their arms, and living in huts that emitted smoke, indicating the mastery of fire. The writer, ostensibly a companion of Herschel named Dr. Andrew Grant, noted that these beavers displayed a level of organization seemingly better than many human tribes.

The climax of the series, however, was the discovery of the Vespertilio-homo, or "Man-Bat." These four-foot-tall beings were covered in copper-colored fur, possessed leathery wings, and were observed engaging in animated conversation. The articles described them sitting near a "Ruby Colosseum," engaging in what looked like polite socialization and even mating rituals. The level of detail was exquisite, painting a picture of a utopia in the sky that captivated a public hungry for wonder.

The Frenzy and the Fallout

The reaction was electric. The Sun’s circulation skyrocketed, surpassing even the Times of London to become the best-selling newspaper in the world for a brief period. Crowds gathered outside the newspaper's offices waiting for the next edition. Yale University professors reportedly traveled to New York to see the original scientific documents. Even rival newspapers, caught on the back foot, reprinted the stories, lending them further credibility.

However, the facade eventually cracked. The articles were not written by a Scottish scientist, but by The Sun’s own reporter, Richard Adams Locke. Locke, a Cambridge-educated journalist, hadn't intended to create a malicious hoax. Rather, he claimed his intent was satire. He was attempting to mock the popular religious-science writing of the time, specifically that of Reverend Thomas Dick, who had calculated that the solar system contained exactly 21,891,974,404,480 inhabitants. Locke wanted to show the absurdity of projecting earthly expectations onto the cosmos.

A Legacy of Wonder

When the truth was revealed, one might expect a riot. Surprisingly, the public reaction was largely one of amusement. New Yorkers, realizing they had been taken for a ride, seemed to appreciate the sheer audacity and entertainment value of the tale. The nickname "The Great Moon Hoax" stuck, but it didn't ruin The Sun; it solidified the paper as a staple of the New York press.

As for Sir John Herschel, who was actually in South Africa staring at the stars (though finding no bat-men), he was initially amused but eventually grew tired of the constant inquiries. He reportedly noted that his actual astronomical observations could never hope to be as exciting as the ones fabricated by Mr. Locke.

The Great Moon Hoax of 1835 stands as a testament to the 19th century's unique intersection of rapid scientific advancement and the explosion of mass media. It was an era where the line between the possible and the impossible was blurring, and for a few days, the people of Earth looked at the moon and saw not a cold, dead rock, but a mirror of their own world—furrier, winged, and infinitely more magical.