The Day the World Exploded: The Apocalyptic Fury of Krakatoa

On the morning of August 27, 1883, the world got smaller, louder, and infinitely more terrifying. In the Sunda Strait, nestled between the islands of Java and Sumatra in what was then the Dutch East Indies, a volcanic island named Krakatoa tore itself apart with such violence that it altered the planet's atmosphere, geography, and collective consciousness. While the 19th century was an era of industrial noise—of steam whistles, factory gears, and cannon fire—nothing humanity had produced could compare to the cataclysm that unleashed the loudest sound in recorded history.

The Roar Heard 'Round the World

At 10:02 a.m., the volcano reached its crescendo. The explosion was estimated to be equivalent to 200 megatons of TNT—roughly four times the yield of the Tsar Bomba, the most powerful nuclear device ever detonated. The shockwave was so intense that it ruptured the eardrums of sailors on the British ship Norham Castle, located 40 miles away. But the sound didn't stop there. It traveled across the Indian Ocean, startling people in Alice Springs, Australia, and was clearly heard on the island of Rodrigues near Mauritius, nearly 3,000 miles away. To put that in perspective, it would be like hearing a noise in Dublin, Ireland, that originated in Boston, Massachusetts. The pressure wave circled the globe seven times, registered by barometers in cities as far-flung as London and Calcutta.

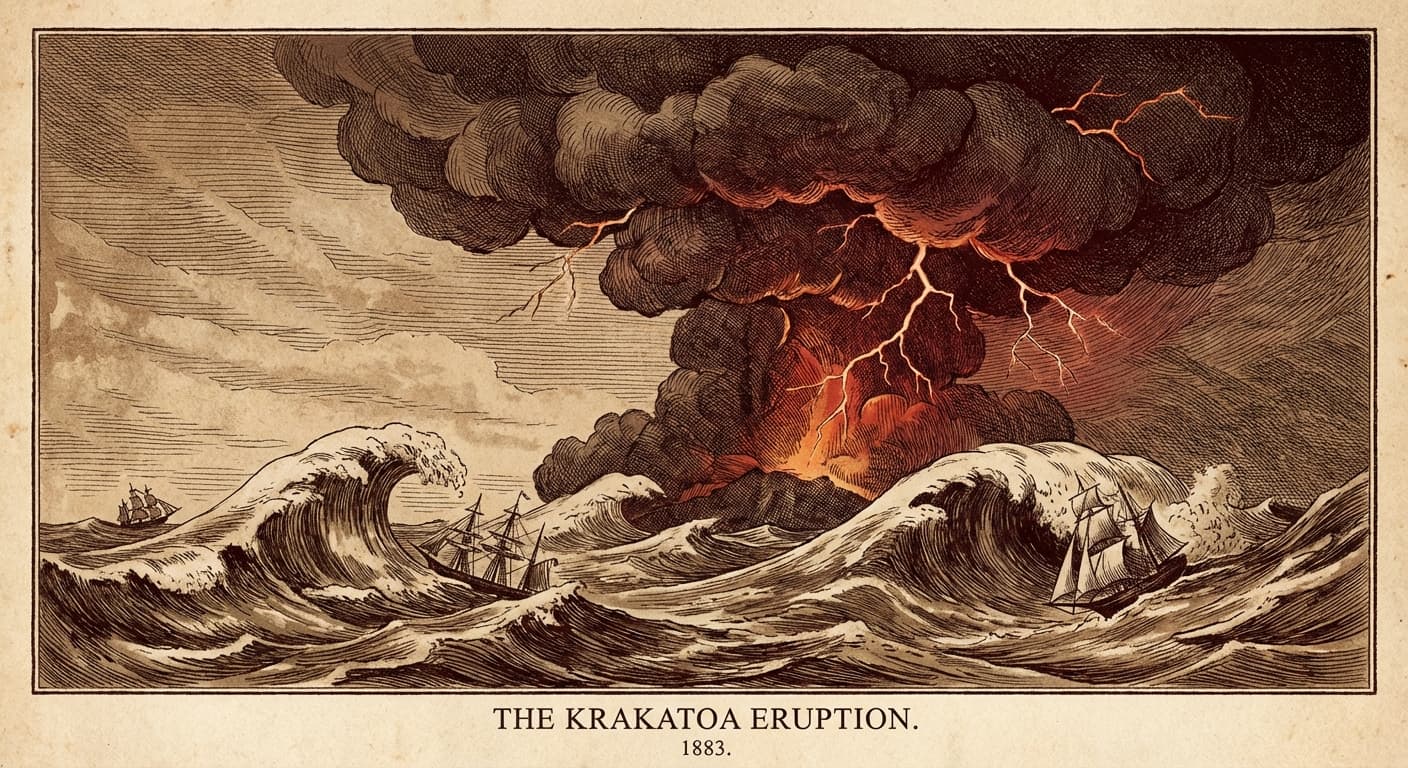

The Wrath of the Sea

While the sound was frightening, the water was deadly. The collapse of the volcano into the caldera displaced a monumental volume of seawater, generating tsunamis that reached heights of over 100 feet. These walls of water decimated 165 coastal villages in Java and Sumatra. The Dutch colonial authorities, usually meticulous in their record-keeping, were overwhelmed by the devastation. The official death toll was recorded at 36,417, though modern estimates suggest the number was likely much higher. Entire settlements were wiped off the map in minutes, with coral blocks weighing 600 tons hurled inland by the sheer force of the waves. The tragedy remains one of the deadliest volcanic events in human history.

The First Global Media Event

Krakatoa was not just a geological event; it was a watershed moment for the information age. By 1883, the world was crisscrossed by a network of submarine telegraph cables—the "Victorian Internet." Unlike the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815, news of Krakatoa traveled at the speed of electricity. Reports from Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) were tapped out in Morse code and printed in newspapers in London, New York, and Paris within hours. For the first time, humanity shared a disaster in real-time. Readers in comfortable Victorian parlors followed the unfolding tragedy day by day, creating a sense of global empathy and interconnectedness that had previously been impossible.

Painting the Sky

The volcano’s reach extended far beyond the immediate blast zone. The explosion ejected approximately five cubic miles of rock, ash, and pumice into the atmosphere. This debris rose 50 miles into the stratosphere, spreading a veil of dust around the globe that lingered for years. This atmospheric curtain filtered sunlight, dropping global temperatures by as much as 2.2 degrees Fahrenheit (1.2 degrees Celsius) over the next year. But it also created a haunting beauty. For months, the world experienced spectacularly vivid sunsets—blazing crimsons, eerie purples, and deep oranges.

These optical phenomena were so intense that fire brigades in Poughkeepsie, New York, were called out to extinguish a fire that didn't exist; the "flames" were merely the sun setting through volcanic ash. Art historians believe this global atmospheric distortion is immortalized in Edvard Munch’s famous painting, The Scream. Painted a decade later but based on a memory from 1883, the blood-red sky that tormented Munch was likely a direct result of Krakatoa’s fury.

The Aftermath

Today, the original island of Krakatoa is gone, obliterated in the 1883 cataclysm. However, in 1927, a new island breached the surface of the caldera. Named Anak Krakatau (Child of Krakatoa), it grows taller every year, a smoking, rumbling reminder of the geologic violence simmering beneath the Earth's crust. The eruption of 1883 served as a humbling check on 19th-century arrogance. In an era where humanity believed it was conquering nature through steam and steel, the Earth reminded us that we are merely tenants living on a volatile, shifting roof. Krakatoa was the moment the Victorian world looked up, covered its ears, and realized just how fragile civilization truly is.