The Day the Sky Burned: The Carrington Event of 1859

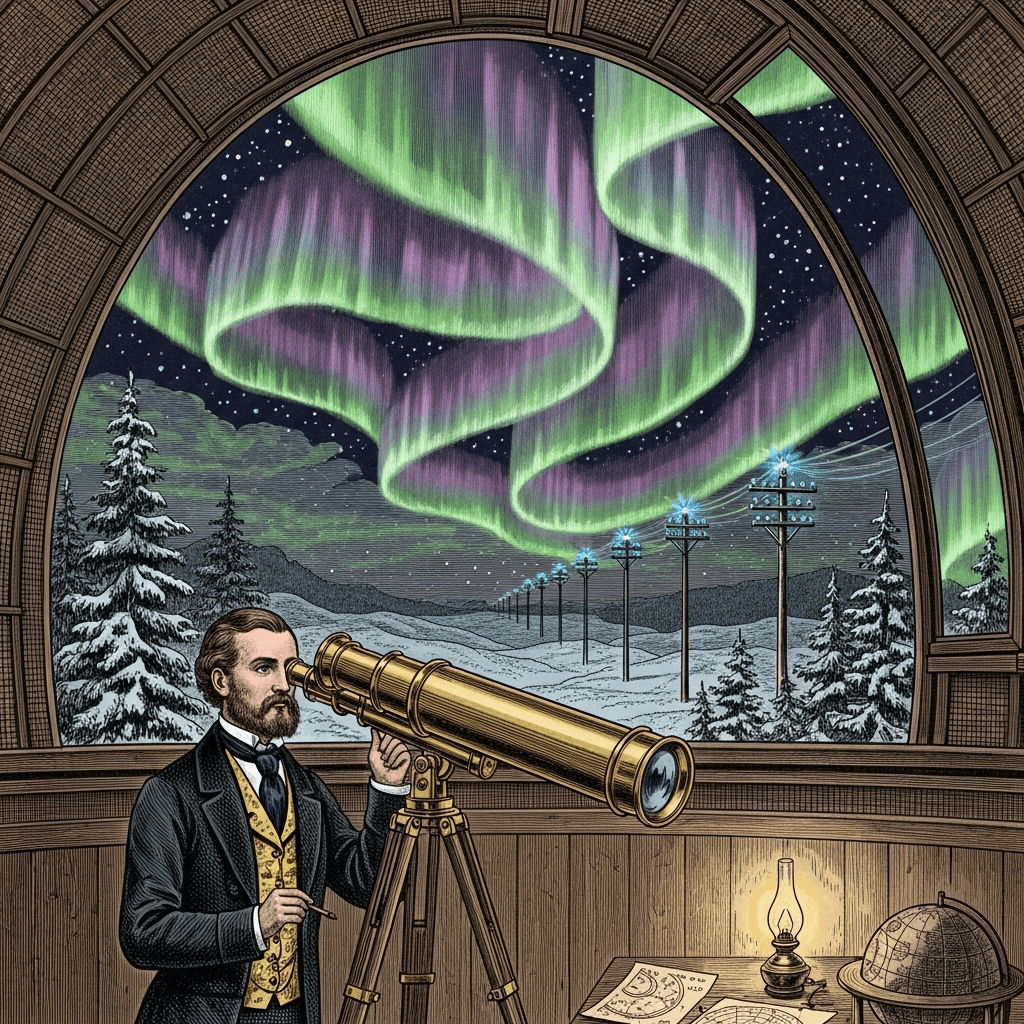

On the quiet morning of September 1, 1859, Richard Carrington, a wealthy amateur astronomer, climbed into his private observatory in Redhill, Surrey. He pointed his brass telescope toward the sun, projecting its image onto a plate of glass to sketch the sunspots that marred the solar surface. It was a routine he had performed countless times, capturing the brooding dark patches that danced across the star. But at 11:18 a.m., something impossible happened. Two patches of intensely bright white light erupted within a large group of sunspots. They were so brilliant that they outshone the sun itself. Carrington, startled and thinking a stray beam of light had entered the telescope, ran to fetch a witness. By the time he returned a minute later, the blinding spectacle was already fading. He didn't know it yet, but he had just witnessed the largest solar flare in recorded history.

What followed in the hours and days to come would go down in history as the Carrington Event, a geomagnetic storm of such ferocity that it turned the night into day and brought the nascent age of electricity to its knees. While Carrington was struggling to make sense of what he had seen, the coronal mass ejection—a billion-ton cloud of magnetized plasma—was hurtling toward Earth at millions of miles per hour. Usually, these solar particles take days to reach our planet; this one arrived in just under eighteen hours, slamming into Earth’s magnetic field with the force of a cosmic sledgehammer.

The effects were immediate and surreal. As night fell over the Americas, the sky erupted in color. Auroras, usually reserved for the polar regions, cascaded down latitudes where they had no business appearing. The Northern Lights were seen as far south as Cuba, the Bahamas, and Hawaii. In the Rocky Mountains, the glow was so bright that miners awoke and began preparing breakfast, thinking it was dawn. Newspapers reported that people in the northeastern United States could read print by the light of the aurora alone. The sky pulsed with blood-red, green, and purple hues, creating a celestial panorama that terrified those who interpreted it as a divine omen of the apocalypse.

However, for the operators of the Victorian era's most advanced technology—the telegraph—the light show was a nightmare. The geomagnetic storm induced massive electrical currents in the copper wires stretching across continents. Telegraph offices became scenes of chaos. Operators reported streams of fire erupting from their equipment. Some received severe electric shocks, while others found that the telegraph paper caught fire spontaneously. In a bizarre twist, some operators discovered they could disconnect their batteries entirely and send messages using only the "auroral current" surging through the lines. For hours, the world's communication network was possessed by the sun itself, ghost-writing messages across the globe through the raw power of a solar storm.

The Carrington Event serves as a humbling reminder of our star's volatility. In 1859, society was only just beginning to rely on electricity. The damage was limited to fried telegraph wires and confused operators. If a storm of similar magnitude were to hit today, the consequences would be catastrophic. Our modern world is wrapped in a fragile web of power grids, satellites, and GPS systems. A repeat of the 1859 event could melt transformers, knock out global communications, and plunge vast areas of the planet into a blackout lasting months or even years. It is a stark juxtaposition: the same solar mechanics that painted the Victorian skies with beautiful terror pose an existential threat to the digital age.

Richard Carrington’s observation on that September morning linked the sun's activity to Earth's magnetic disturbances for the first time, birthing the field of space weather. While the 19th century is often remembered for the grind of the Industrial Revolution and the smoke of factories, the Carrington Event reminds us that it was also a time when humanity first came face-to-face with the cosmic forces governing our existence. It remains a singular moment when the clockwork predictability of the Victorian world was shattered by the raw, untamed fury of the sun.