The Bone Wars: The Petty Feud That Gave Us the Dinosaurs

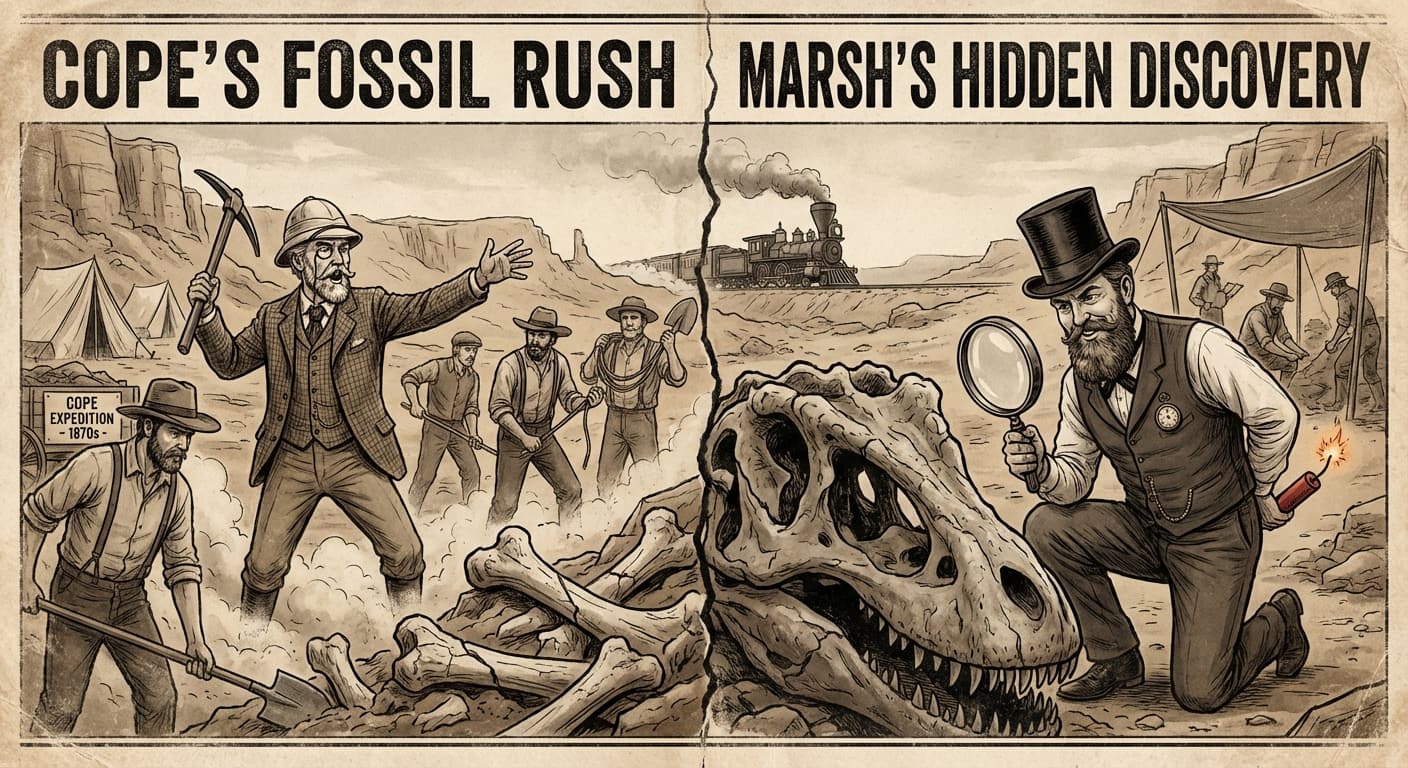

When we imagine the American Wild West, the mind naturally drifts to images of dusty saloons, high-noon duels, and rugged cowboys driving cattle across the plains. But in the late 19th century, the frontier was also the battleground for a different kind of war—one fought not with six-shooters, but with picks, shovels, and dynamite. This was the Great Dinosaur Rush, known to history as the ‘Bone Wars.’ At the center of this conflict stood two brilliant, wealthy, and utterly ruthless paleontologists: Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh.

Initially, the two men were friends. They met in Berlin in 1864, sharing a mutual passion for the budding science of paleontology. They even named fossil species after one another in a show of gentlemanly respect. However, the truce was fragile, built on the unstable ground of massive egos. The relationship shattered irrevocably in 1868, thanks to a prehistoric marine reptile called the Elasmosaurus.

Cope, a prodigy from the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, had reconstructed the skeleton of this long-necked creature. In a rush to publish his findings, he made a humiliating anatomical error: he placed the animal's skull at the end of its tail, mistaking the short neck for the tail and the long tail for the neck. When Marsh, a professor at Yale, pointed out the mistake publicly—and reportedly laughed about it—Cope was mortified. He attempted to buy back every copy of the journal containing the error, but the damage was done. The friendship evaporated, replaced by a vitriolic hatred that would consume the rest of their lives.

What followed was a decades-long competition to discover and name the most dinosaur species. The battlefield was the fossil-rich sediment of Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming. Marsh and Cope didn’t just try to outwork each other; they tried to destroy each other. They used their personal fortunes to bribe each other's field crews, spy on dig sites, and steal shipments of bones. In one of the most heartbreaking acts of scientific vandalism in history, both men were known to order their teams to dynamite fossil quarries after they were finished with them, simply to ensure the other could not harvest any remaining bones.

They took their war to the press, publishing slanderous articles in the New York Herald, accusing one another of plagiarism, incompetence, and financial impropriety. The scientific community watched in horror and fascination as these two titans dragged the reputation of American paleontology through the mud. Marsh eventually used his political connections in Washington to cut off Cope's government funding, nearly ruining him financially.

Yet, for all the toxicity, the Bone Wars were ironically productive. Before the feud began, there were only nine named species of dinosaurs in North America. By the time the dust settled and both men had died—broke and bitter—they had identified over 130 new species. Some of the most iconic dinosaurs we know today, including Triceratops, Stegosaurus, Diplodocus, and Allosaurus, were discovered during this frenzied race for glory.

The rivalry didn't even end with death. Before he died in 1897, Cope issued a final challenge. He donated his skull to science, instructing that his brain size be measured, hoping it would be larger than Marsh's. He was convinced that cranial capacity correlated with intelligence and wanted one final, posthumous victory. Marsh, perhaps wisely, never accepted the challenge.

Today, the Bone Wars serve as a cautionary tale about the perils of ego in science. While their methods were often deplorable and their haste led to decades of taxonomic confusion that later scientists had to clean up, Marsh and Cope undeniably sparked the world's enduring fascination with dinosaurs. They opened a window into the deep past, even if they had to smash it with a hammer to do so.