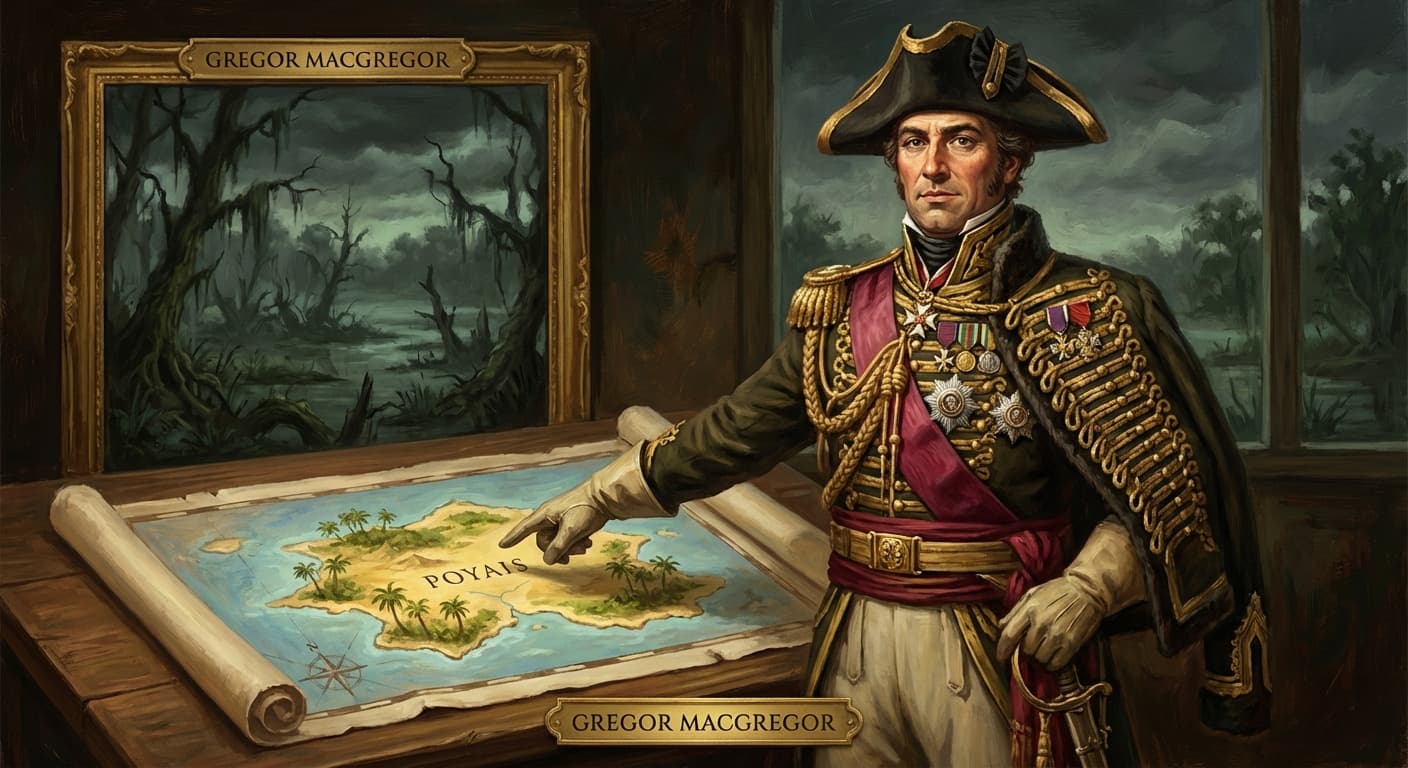

The Prince of Nowhere: How Gregor MacGregor Sold a Country That Didn't Exist

In the annals of history, confidence tricksters hold a special, if somewhat notorious, place. We are often fascinated by the sheer audacity of those who can look the world in the eye and sell it a lie. But few con artists in history can hold a candle to Gregor MacGregor, the Scottish soldier-turned-adventurer who pulled off one of the most elaborate and devastating frauds of the 19th century. In the 1820s, MacGregor didn’t just sell a bridge or a non-existent gold mine; he sold an entire country.

To the people of London in 1822, Gregor MacGregor was a hero. He was a dashing figure, a veteran of the Peninsular War and a general in the Venezuelan War of Independence, where he had fought alongside Simon Bolivar. When he returned to Britain, he brought with him more than just war stories. He arrived with a title—"Cazique" (Prince)—and a deed to a vast territory on the Mosquito Coast of Central America known as Poyais. According to MacGregor, Poyais was a veritable Eden. It was a land where chunks of gold lined the riverbeds, the soil was so fertile it could yield three maize harvests a year, and the natives were not only friendly but eager for British governance.

MacGregor’s sales pitch was masterfully comprehensive. He didn't just talk about Poyais; he fabricated it into existence through bureaucracy. He opened a distinct legation office in London to handle the affairs of the young nation. He commissioned a 355-page guidebook, penned under the pseudonym Thomas Strangeways, which detailed the country’s capital, St. Joseph, describing its broad boulevards, opera house, cathedral, and deep-water port. He had official Poyaisian currency printed and even composed a national anthem. To the investment-hungry British public, flush with cash from the Industrial Revolution and looking for high yields in the Americas, Poyais seemed like the opportunity of a lifetime.

Caught up in the "bubble" mania of the era, hundreds of people bought into the dream. MacGregor sold huge tracts of land to Scottish Highlanders who were desperate to escape poverty. He floated a sovereign loan on the London stock exchange, raising nearly £200,000 (a staggering sum equivalent to tens of millions today). The legitimacy of the scheme was bolstered by MacGregor’s own charm and his connections to high society. Who would doubt a war hero with such detailed maps and official-looking documents?

The tragedy began in late 1822 and early 1823, when two ships, the Honduras Packet and the Kennersley Castle, set sail for the promised land. Onboard were around 250 hopeful settlers, ranging from cobblers and doctors to bankers and farmers, many of whom had liquidated their life savings to buy land in MacGregor’s paradise. They carried with them the colorful Poyaisian banknotes they had exchanged for their sterling, expecting to spend them in the markets of St. Joseph.

When the ships arrived at the coordinates of Poyais, the settlers were met with a horrific silence. There was no deep-water port. There were no broad boulevards, no opera house, and certainly no gold. There was only an impenetrable, swampy jungle and a few bewildered indigenous people who had no idea what a "Cazique" was. St. Joseph was nothing more than a desolate stretch of mud and ruins. The settlers initially assumed there had been a mistake, perhaps a navigational error, but the grim reality soon set in. They had been dumped on a malaria-ridden coast with few provisions.

The situation deteriorated rapidly. The would-be colonists attempted to build shelter, but the rainy season and tropical diseases ravaged their numbers. Malaria and yellow fever swept through the camp. The provisions they had brought were ruined by the humidity. It wasn’t until a ship from British Honduras (modern-day Belize) spotted them months later that a rescue was mounted. By then, the damage was catastrophic. Of the roughly 250 settlers who had sailed to Poyais, two-thirds died in the jungle. The survivors returned to London as broken specters of the optimistic pioneers they had once been.

Perhaps the most shocking aspect of the Poyais scheme was the aftermath. When the survivors returned with their harrowing tales, MacGregor was not immediately lynched or imprisoned. In an incredible twist of gaslighting, he publicly blamed the settlers for the failure, claiming they had been ill-prepared and had not followed his instructions. While public opinion eventually turned against him, the legal system found it difficult to pin down the fraudster, partly due to the complex nature of international sovereignty and land grants.

Unbelievably, MacGregor fled to Paris and attempted to run the exact same scam again. He tried to sell Poyais to the French, though this time he was less successful; the French authorities were more suspicious and eventually imprisoned him for fraud. He was later acquitted and returned to London, where he continued to dabble in minor schemes before retiring to Venezuela. There, his past service in the wars of independence earned him a pension and a hero’s burial upon his death in 1845.

Gregor MacGregor remains a singular figure in the history of fraud. While Ponzi gave his name to a scheme and Eiffel tried to sell a tower, MacGregor invented a nation, complete with a flag, a government, and a geography, solely to rob the hopeful. The Kingdom of Poyais remains the phantom country that never was, a testament to the power of greed and the dangerous allure of a perfect world.