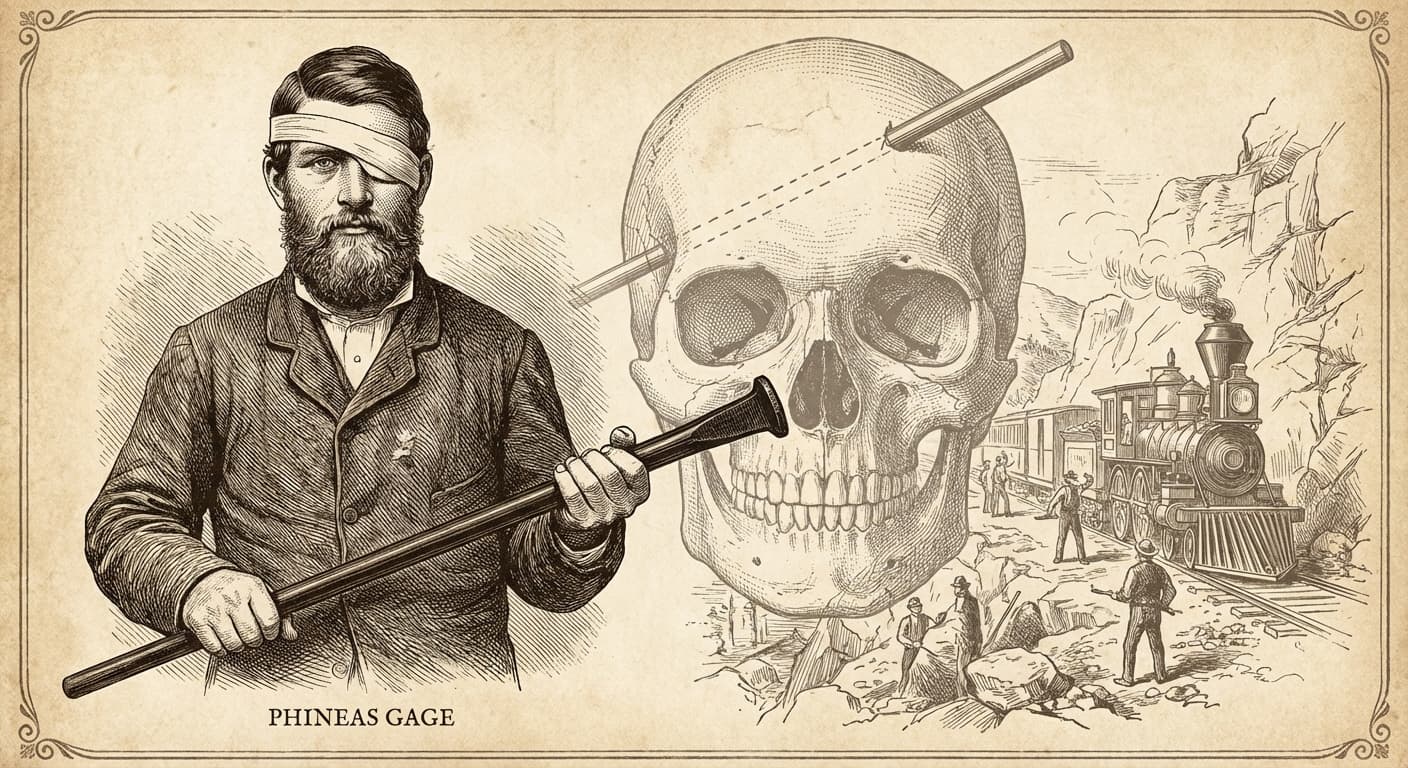

The Man Who Survived the Impossible: Phineas Gage and the Birth of Neuroscience

On a crisp afternoon in September 1848, near the town of Cavendish, Vermont, a twenty-five-year-old railway foreman named Phineas Gage stood over a blasting hole, distracting himself for a fraction of a second too long. In that fleeting moment, the course of his life—and the future of brain science—changed irrevocably. The story of Phineas Gage is not merely a tale of survival; it is a gruesome medical curiosity that shattered the 19th-century understanding of the human mind and proved that our personalities are physically tethered to the gray matter within our skulls.

The Accident That Should Have Killed Him

Gage was known as a capable, efficient, and well-liked foreman working on the Rutland & Burlington Railroad. His job was dangerous but routine: clearing rocks to level the ground for tracks. The process involved drilling holes into stone, filling them with blasting powder, inserting a fuse, and then packing sand on top (tamping) to direct the blast downward. On this specific day, Gage was using a custom-made tamping iron—a javelin-like crowbar measuring 3 feet 7 inches long and weighing over 13 pounds.

Distracted by men working behind him, Gage turned his head. The iron struck the rock, creating a spark. The powder ignited. The resulting explosion didn't just crack the stone; it turned the tamping iron into a missile. The rod entered just under Gage’s left cheekbone, smashed behind his left eye, plowed through the left frontal lobe of his brain, and exited through the top of his skull. The iron landed some 80 feet away, smeared with blood and brain matter.

By all medical logic of 1848, Phineas Gage should have died instantly. Instead, he was thrown backward, convulsed briefly, and then—miraculously—sat up. Within minutes, he was speaking. He rode in an oxcart to a nearby hotel, where he reportedly sat on the veranda and told the responding physician, Dr. Edward H. Williams, "Doctor, here is business enough for you."

The Medical Miracle

The treatment of Phineas Gage was undertaken by Dr. John Martyn Harlow, whose detailed notes provide the historical record of this event. Harlow managed to stop the hemorrhaging and treated the inevitable infection and brain swelling that followed. For weeks, Gage hovered between life and death, slipping into a coma at one point. His family even prepared a coffin. Yet, his robust constitution prevailed. By November, he was walking around town. By the following year, he was physically recovered, save for the loss of vision in his left eye.

However, while the physical wounds healed, the man who returned was different. Before the accident, Gage was described as shrewd, energetic, and persistent. Afterward, Dr. Harlow noted a profound shift. Gage became fitful, irreverent, and indulged in the grossest profanity (which was previously not his custom). He was impatient, obstinate, and unable to stick to plans. His friends and previous employers noted sadly that "Gage was no longer Gage."

The Birth of Localized Brain Function

In the mid-19th century, the prevailing scientific view was that the brain functioned as a single, undifferentiated organ, or conversely, was best understood through phrenology (measuring bumps on the skull). Gage’s case provided the first significant clinical evidence that specific areas of the brain controlled specific functions. Because the tamping iron had destroyed his left frontal lobe while leaving his motor skills, memory, and speech largely intact, it suggested that the frontal cortex was the seat of personality, social inhibition, and planning.

This realization was revolutionary. It moved psychology from the realm of the soul and metaphysics into the realm of biology. Gage became the accidental index case for the study of the prefrontal cortex.

A Life After the Legend

Contrary to some exaggerated myths that Gage became a destitute drifter, recent historical research suggests he struggled but eventually adapted. After losing his railroad job due to his personality changes, he exhibited himself at P.T. Barnum's American Museum in New York for a time—proudly holding the tamping iron that had pierced his skull.

Eventually, he traveled to Chile, where he worked as a long-distance stagecoach driver for seven years. This role required complex planning and social interaction with passengers, suggesting that his brain may have eventually regained some of its lost functions—a testament to the brain's plasticity. In 1860, his health began to fail, and he suffered a series of epileptic seizures, likely a long-term consequence of the trauma. He died in San Francisco at age 36.

The Legacy of the Tamping Iron

Today, Phineas Gage’s skull and the famous tamping iron are on display at the Warren Anatomical Museum at Harvard Medical School. They remain pilgrimage sites for neurologists and psychologists. While 19th-century science couldn't save his personality, Phineas Gage saved science from ignorance. He taught the world that the essence of who we are—our morals, our temperaments, our very selves—is etched into the delicate electric fabric of our brains.