The Merchant of Death Who Bought Peace: How a Premature Obituary Created the Nobel Prize

In the history of second chances, few are as consequential—or as expensive—as the one granted to Alfred Nobel. Today, the name "Nobel" is synonymous with the pinnacle of human achievement, evoking images of laureates accepting gold medals for advancements in physics, literature, and peace. However, had you asked the average European citizen about the name in the mid-19th century, the association would have been far darker. They would have thought of smoke, shattered rock, and the terrifying power of high explosives. The story of how the inventor of dynamite pivoted from a legacy of destruction to one of global betterment is a fascinating tale of mistaken identity, existential dread, and a desperate bid for redemption.

Alfred Nobel was born into a family of engineers and entrepreneurs in Stockholm in 1833. Science ran in his blood, but so did danger. His father, Immanuel, was an inventor who experimented with naval mines and explosives. Following in his father's footsteps, Alfred became obsessed with nitroglycerin, a highly volatile liquid explosive discovered by Ascanio Sobrero. Nitroglycerin was powerful but notoriously unstable; a slight jolt or a rise in temperature could cause catastrophic detonations. Alfred witnessed this horror firsthand in 1864 when a shed at the family factory in Heleneborg exploded, killing five people, including his younger brother, Emil. Rather than deterring him, the tragedy galvanized Alfred to tame the beast.

Through relentless experimentation, Alfred discovered that mixing liquid nitroglycerin with a porous, absorbent sand called kieselguhr (diatomaceous earth) created a paste that was stable, malleable, and safe to transport. He patented this invention in 1867 under the name "dynamite." It was a revolution. Suddenly, blasting tunnels through mountains, clearing canals, and building railways became exponentially faster and safer. The Industrial Revolution found its new hammer, and Nobel became one of the wealthiest men in the world. But dynamite, naturally, also found its way into the arsenals of armies. Nobel’s factories dotted the globe, churning out the fuel for modern warfare, earning him a reputation as a profiteer of violence.

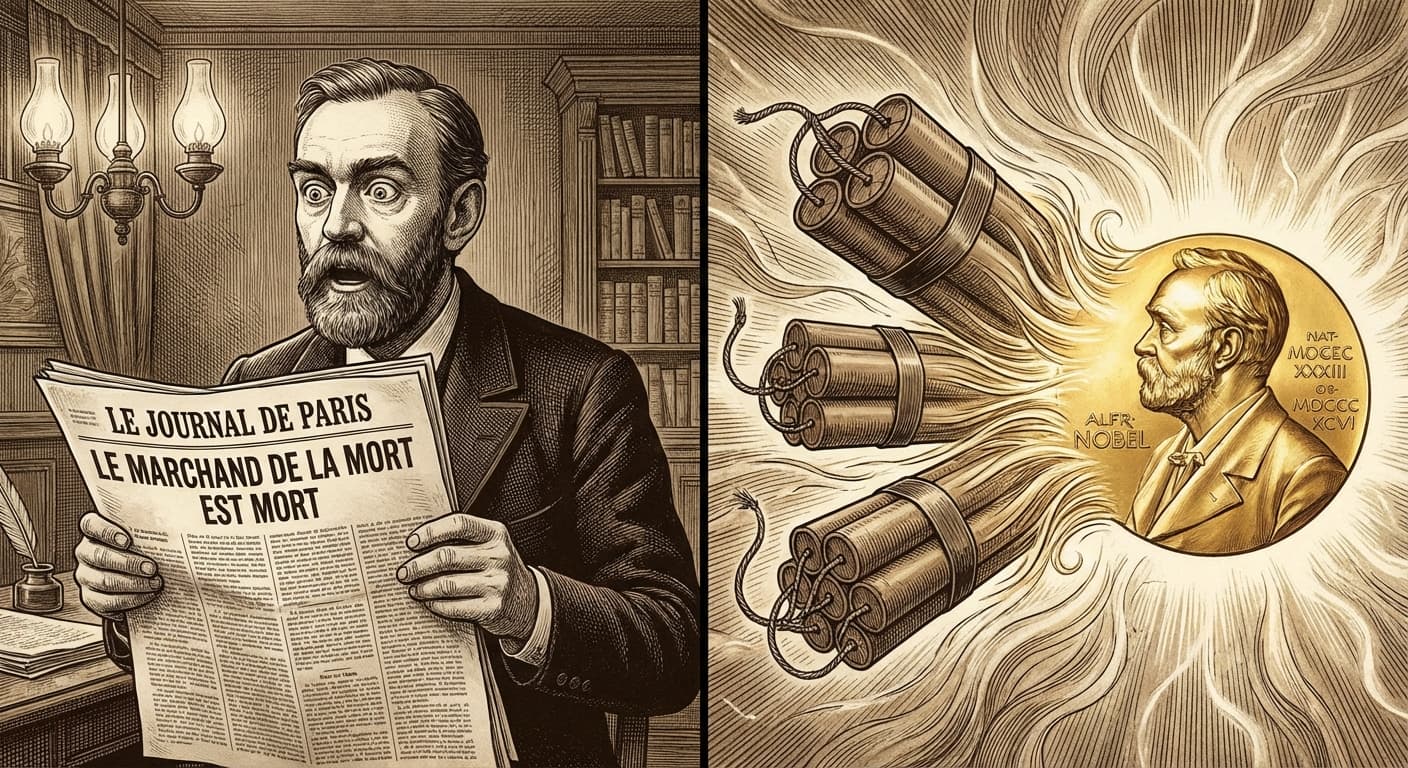

The turning point came on a spring morning in 1888, in Cannes, France. Alfred’s brother, Ludvig, had died of a heart attack while visiting the city. In a twist of fate that would change history, a French newspaper confused the two brothers. Thinking the inventor of dynamite had died, they published an obituary for Alfred instead of Ludvig. When Alfred opened the newspaper that morning to read about his brother's passing, he was instead confronted with a scathing summary of his own life. The headline screamed: "Le marchand de la mort est mort" ("The Merchant of Death is Dead").

The article went on to describe him as a man who had "become rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before." Alfred was horrified. He sat there, alive and breathing, holding a paper that told him exactly how the world would remember him. The label "Merchant of Death" cut deep. He was a complex man—a pacifist at heart who justified his inventions by claiming they would make war so terrible that nations would abandon it immediately (a logic that would later be echoed, and disproven, by the atomic bomb). The obituary shattered his delusions. He realized that without intervention, his legacy would be nothing but blood and rubble.

Haunted by the prospect of being vilified by future generations, Nobel spent his final years quietly planning a massive course correction. He didn't marry and had no children, leaving him free to do with his fortune as he pleased. When he died—for real this time—in 1896, his family and the public were stunned when his last will and testament was read. He had secretly allocated 94% of his total assets, approximately 31 million Swedish kronor (a staggering sum at the time), to establish a series of five prizes.

The will stipulated that the interest on the fund should be distributed annually to those who, during the preceding year, "shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind." He specified categories for Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature, and, most surprisingly to his critics, Peace. The Peace Prize was to go to the person who had done the most for "fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses."

The establishment of the prizes was not a smooth process. His family contested the will, the King of Sweden, Oscar II, was initially offended that the prizes could be awarded to non-Scandinavians, and the designated institutions were hesitant to take on the responsibility. Yet, the will held firm. In 1901, five years after his death, the first Nobel Prizes were awarded. The man who had revolutionized destruction had successfully purchased a legacy of creation. Today, when we hear the name Nobel, we think of the cure for diseases, the poetry of great writers, and the cessation of conflict—proving that while you cannot change the past, with enough foresight (and capital), you can certainly rewrite the future.