The Last American Vampire: The Haunting Exhumation of Mercy Brown

When we think of vampires in the 19th century, our minds instinctively drift to the foggy, cobblestone streets of Victorian London or the foreboding castles of Transylvania, fueled by the literary genius of Bram Stoker. However, just five years before Stoker published Dracula, a very real, very terrifying vampire hunt was taking place not in Europe, but in the quiet farming community of Exeter, Rhode Island.

It was 1892, a time when the world was pivoting toward modernity. The electric light bulb had been invented, automobiles were on the horizon, and germ theory was gaining acceptance in medical circles. Yet, in the rural corners of New England, ancient superstition held a chilling grip on the populace. This is the story of Mercy Brown, the teenager who became the central figure of the Last Great Vampire Panic in America.

The Shadow of the White Plague

To understand why a grieving father would agree to dig up his own daughter, one must understand the enemy they were fighting. Tuberculosis, known then as "consumption," was the leading cause of death in the 19th century. It was a horrifying disease that seemed to eat the victim from the inside out. Sufferers became pale and gaunt, their eyes sank into their sockets, and they coughed up blood. As they wasted away, it appeared as though their life force was being drained by an invisible predator.

In New England folklore, this draining had a supernatural explanation. If one family member died of consumption, and then another fell ill shortly after, it was believed that the deceased was not truly dead. Instead, they were lingering in the grave, feeding on the vitality of their living kinsmen to sustain their own unnatural existence.

The Tragedy of the Brown Family

George Brown was a farmer who had seen too much death. In the late 1880s, the "white plague" swept through his home. First, it claimed his wife, Mary. Next, it took his eldest daughter, Mary Olive. In January 1892, his 19-year-old daughter, Mercy Lena Brown, succumbed to the illness. George was left with his son, Edwin, a young man with a bright future who worked as a store clerk. But shortly after Mercy’s funeral, the pattern repeated: Edwin began to cough. He grew weak. The shadow had returned.

Desperate and terrified, the neighbors approached George. They whispered that one of the three women buried in the family plot was responsible—a vampire feasting on Edwin from beyond the grave. George Brown, described as a practical man who likely didn't believe in such superstitions, was nonetheless a father willing to do anything to save his only remaining child. He gave his consent for the exhumations.

The Exhumation

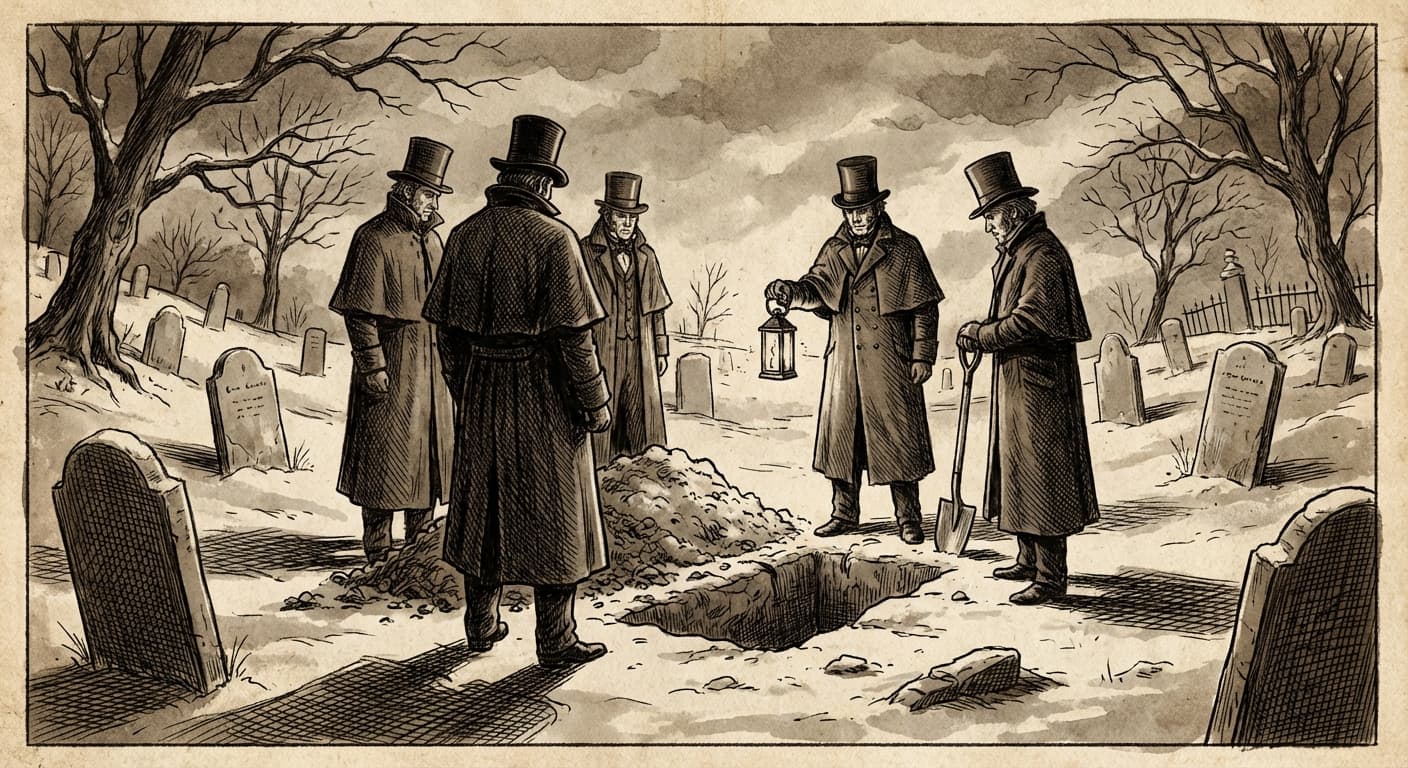

On the morning of March 17, 1892, a group of men, accompanied by the town doctor and a newspaper correspondent, entered the snowy graveyard. They dug up the bodies of Mary and Mary Olive. Both were little more than skeletons, their decomposition consistent with the time they had been buried. They were cleared of suspicion.

Then, they turned their shovels to Mercy Brown. She had been dead for only two months, buried during the freezing chaos of a New England winter. When they pried open the coffin, the onlookers gasped. Mercy lay on her side. Her face was flushed, her hair and nails appeared to have grown, and most damning of all, there was liquid blood in her heart and liver.

To the superstitious villagers, this was undeniable proof. She was fresh. She was feeding. To the doctor present, it was merely the result of the body being stored in an above-ground crypt during freezing temperatures, acting as a natural refrigerator that slowed decomposition. But science held no sway over fear that day.

The Ritual and the Aftermath

Following the grim dictates of tradition, the men cut out Mercy’s heart and liver. They burned the organs on a nearby rock until they were nothing but ash. These ashes were then mixed with water to create a tonic, which the dying Edwin was forced to drink. It was believed that consuming the vampire's remains would break the curse and cure the victim.

It did not work. Edwin Brown died two months later, the last victim of the tuberculosis outbreak in the Brown household.

Mercy’s body was reburied, but her story did not stay in the grave. The incident made headlines across the globe, viewed by urbanites as a shocking display of primitive ritual in a modernizing nation. It is even rumored that newspaper clippings of the event were found in the possession of Bram Stoker, potentially influencing the lore of Dracula, particularly the character of Lucy Westenra.

The exhumation of Mercy Brown stands as a haunting bookmark in history—a collision between the folklore of the past and the medical science of the future. It serves as a tragic reminder of how fear and grief can drive rational people to do the unthinkable, searching for monsters in the earth when the true killer was a microscopic bacillus they could not yet fully conquer.