The Map That Stopped a Killer: How John Snow Solved the Mystery of Cholera

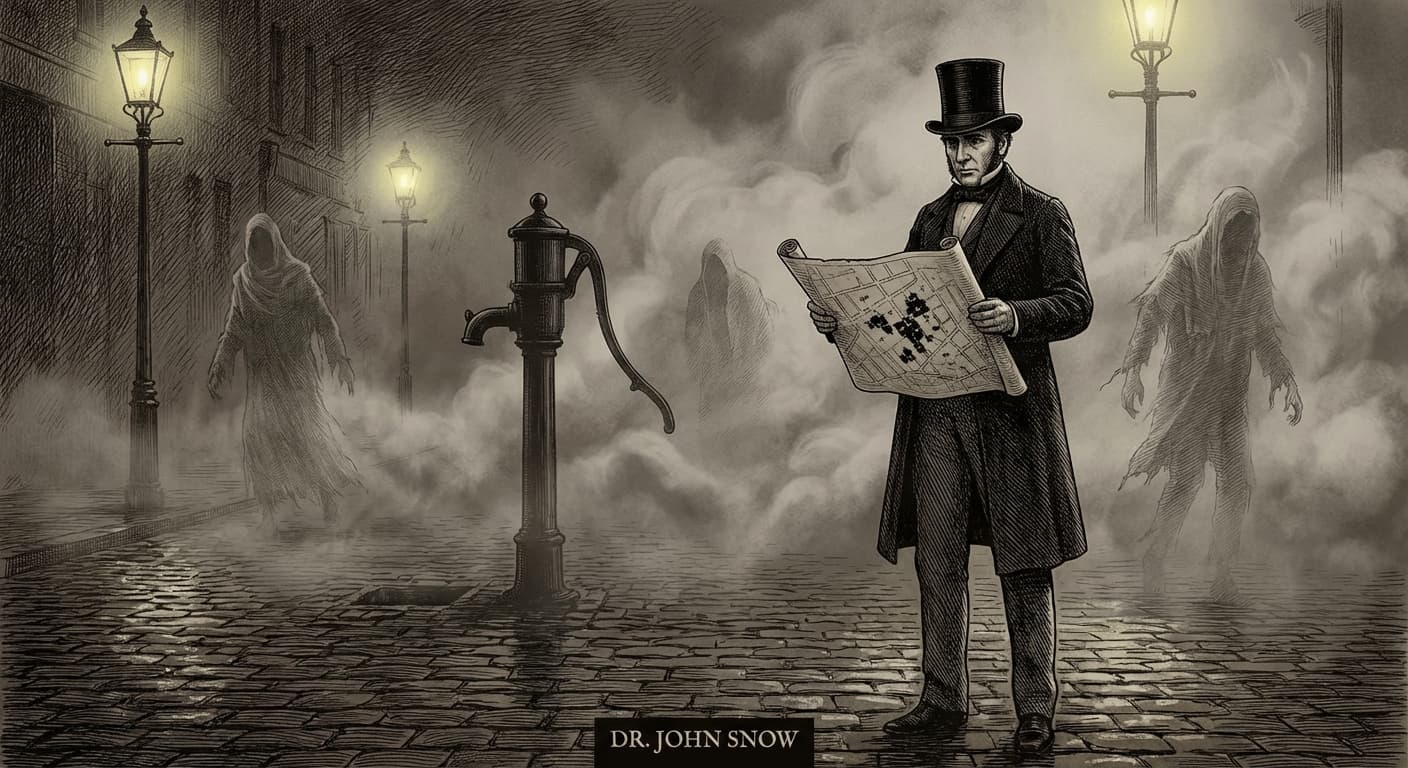

In the mid-19th century, London was a city of unparalleled industry and wealth, yet it was also a city besieged by an invisible, terrifying enemy. This enemy didn't carry a rifle or march in columns; it struck silently, turning healthy men and women into corpses within hours. They called it "King Cholera." In 1854, as a devastating outbreak swept through the Soho district, the accepted medical wisdom of the day failed to halt the slaughter. It would take a quiet, persistent doctor named John Snow, a bit of detective work, and a simple map to challenge centuries of dogma and give birth to modern epidemiology.

To understand the magnitude of Snow's achievement, one must understand the intellectual climate of Victorian medicine. In the 1850s, the germ theory of disease was not yet established. Instead, the medical establishment bowed to the "miasma theory." Doctors, politicians, and public health officials believed that diseases like cholera and the plague were caused by "bad air"—noxious vapors rising from rotting organic matter, open sewers, and the filth of the industrial city. It made intuitive sense in a city as smelly as London, but it was dead wrong. When cholera arrived, authorities urged people to clean up the smells, often inadvertently flushing contaminated waste into the very water sources the population drank from.

John Snow, an obstetrician and anesthetist who had famously administered chloroform to Queen Victoria during childbirth, was a skeptic. He had observed cholera closely and noted that the symptoms—vomiting and diarrhea—suggested a problem with the gut, not the lungs. If the disease were spread by air, surely it would attack the respiratory system. Snow hypothesized that cholera was ingested, likely through water contaminated by fecal matter. But in a world married to the idea of miasma, Snow was a lone voice shouting into the wind.

His theory was put to the ultimate test in late August 1854. A ferocious outbreak erupted in Soho, killing over 120 people in just three days. Panic ensued. Families fled, leaving their homes empty, while the remaining residents watched their neighbors drop one by one. Snow, living near the outbreak, didn't flee. Instead, he went to work. He began a tedious, dangerous process of door-to-door interviewing. He needed data to prove his waterborne theory.

Snow focused his investigation on Broad Street (now Broadwick Street), the epicenter of the death toll. He recorded the location of every death, plotting them as black bars on a map of the neighborhood. As the visual evidence mounted, a chilling pattern emerged. The deaths were not randomly distributed; they were clustered tightly around a single public water source: the Broad Street Pump. The pump was popular; its water was known for being cooler and more carbonated than rival pumps. But Snow's map revealed it was the source of the poison.

Crucially, Snow's detective work also identified the anomalies that proved the rule. He found a local workhouse just around the corner from the pump that had suffered almost no deaths. Upon investigation, he learned they had their own private well. Similarly, a local brewery on Broad Street had been spared. When Snow interviewed the workers, they told him they drank the malt liquor they produced, or water from the brewery’s own well, never touching the public pump. He even tracked down a death in a distant part of London—a widow who had once lived in Soho and liked the Broad Street water so much she paid to have a bottle delivered to her daily. She and her niece, who drank from the same bottle, both died of cholera.

Armed with his map and his data, Snow approached the local Board of Guardians on September 7, 1854. He presented his evidence and made a simple, practical recommendation: remove the handle from the Broad Street Pump. The board was skeptical of his theory but desperate enough to agree. The handle was removed, and the outbreak, which was already waning, ended almost immediately.

Later investigations vindicated Snow completely. A local curate, Henry Whitehead, initially tried to disprove Snow but ended up finding the "index case": a baby who had contracted cholera days before the major outbreak. The mother had washed the baby’s diapers and tossed the water into a cesspool that leaked directly into the Broad Street Pump's well. The cool, carbonated taste the residents loved? It was the result of organic decomposition.

John Snow died just four years later, in 1858, without seeing his theory fully accepted by the scientific community. It would take another decade and the work of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch to firmly establish the germ theory. However, Snow’s legacy is immortal. By tracing the dots on a map, he did more than just stop an outbreak; he proved that data could save lives. He turned medicine from a philosophy of vague humors into a science of observation and statistics, laying the foundation for public health systems that protect billions today.