The Tragic Prophet of Clean Hands: How Ignaz Semmelweis Saved Mothers and Lost His Mind

In the mid-19th century, entering a hospital to give birth was often a death sentence. Before the advent of germ theory, medical institutions were breeding grounds for infection, and nowhere was this more terrifyingly evident than in the maternity wards of the Vienna General Hospital. It was here, amidst the groans of the dying, that a Hungarian doctor named Ignaz Semmelweis made a discovery that would save countless lives, yet destroy his own in the process. His story is one of brilliant deduction, professional arrogance, and heartbreaking irony.

In 1846, Semmelweis began working as an assistant in the hospital's obstetrics division. The department was split into two clinics: the First Clinic, staffed by male doctors and medical students, and the Second Clinic, staffed by midwives. A chilling statistical anomaly plagued the hospital. In the First Clinic, the mortality rate for mothers from puerperal fever—also known as "childbed fever"—hovered between 10% and sometimes peaked as high as nearly 30%. In contrast, the Second Clinic, right next door, maintained a much lower rate of about 4%. The discrepancy was public knowledge; women begged on their knees not to be admitted to the First Clinic, preferring to give birth in the streets rather than face the "doctors of death."

Semmelweis was tormented by this disparity. The prevailing medical wisdom of the time blamed "miasma" (bad air), overcrowding, or even the chilling sound of the priest’s bell ringing for the dying. But Semmelweis systematically ruled these out. Both clinics shared the same air, the same overcrowding, and the same diet. The only major difference was the personnel. Why were doctors more deadly than midwives?

The grim answer arrived in 1847 through a personal tragedy. Semmelweis’s friend and colleague, Jakob Kolletschka, died after being accidentally pricked by a scalpel during an autopsy. Semmelweis noted that Kolletschka’s autopsy revealed pathology identical to that of the women dying of childbed fever. A lightbulb went on in the darkness of 19th-century ignorance. The doctors and students in the First Clinic often began their days performing autopsies on cadavers before heading directly to the maternity ward to deliver babies. They were carrying invisible "cadaverous particles" on their hands from the morgue to the mothers.

Midwives, notably, did not perform autopsies.

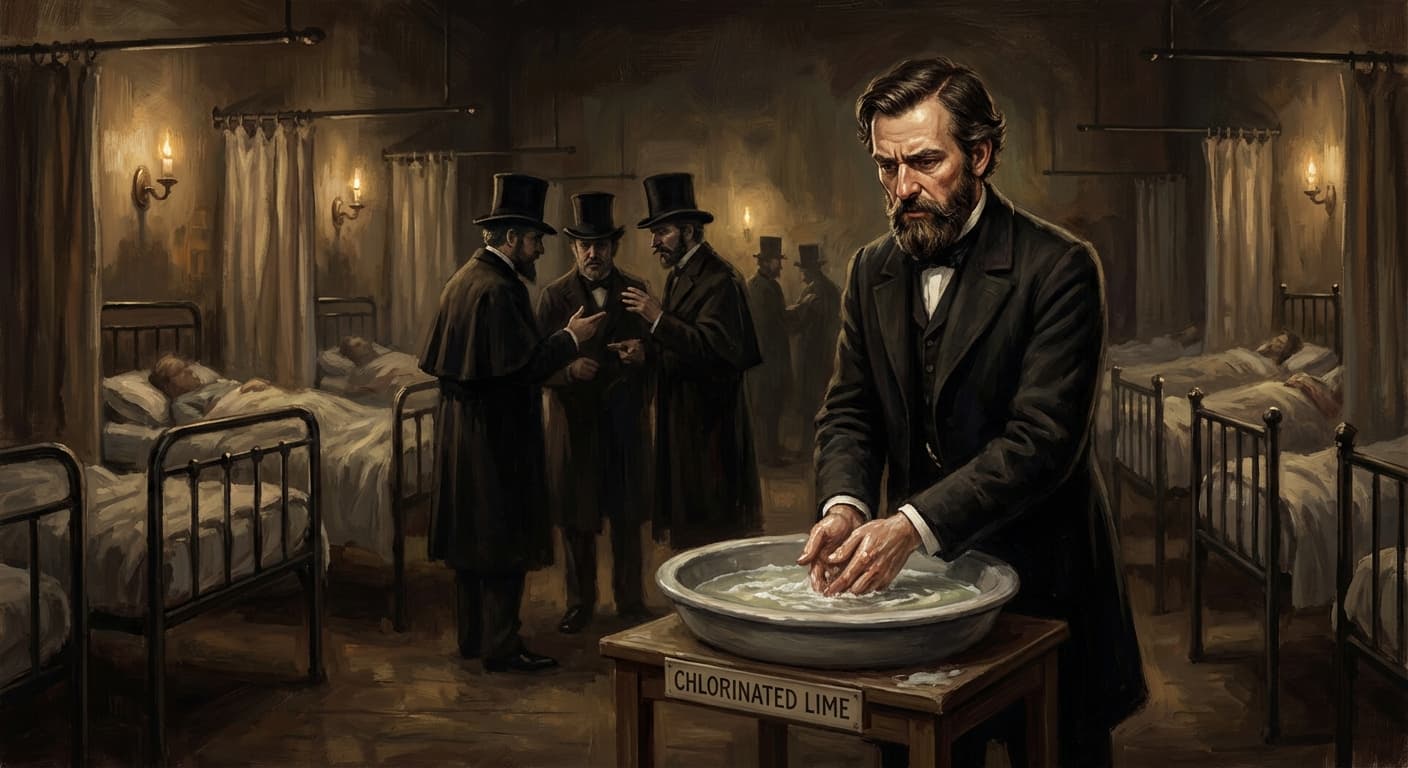

Semmelweis immediately instituted a controversial policy: everyone in the First Clinic was required to wash their hands with a solution of chlorinated lime before examining patients. The results were nothing short of miraculous. By 1848, the mortality rate in the First Clinic plummeted to just over 1%, comparable to that of the midwives' clinic. It was a clear, data-driven victory.

However, instead of being hailed as a hero, Semmelweis faced a vitriolic backlash. His theory challenged the established scientific dogma of miasmas and imbalances in the four humors. More personally, it deeply offended the medical elite. To accept Semmelweis’s findings was to admit that they—gentlemen of high social standing—were responsible for killing their patients with their own unclean hands. One distinct critic stated, "Doctors are gentlemen, and a gentleman's hands are clean."

Historical timing also worked against him. The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 created political tension in Vienna, and the Hungarian Semmelweis was eventually dismissed from his post. He returned to Budapest, frustrated and increasingly embittered, publishing his findings in a book that was largely ignored or mocked by the luminaries of European medicine, including Rudolf Virchow.

As the years passed, Semmelweis’s mental health deteriorated under the weight of rejection and the knowledge that women continued to die unnecessarily. He became obsessive, writing angry, open letters to prominent obstetricians, accusing them of being "irresponsible murderers." His behavior became increasingly erratic, and in 1865, his colleagues lured him to an asylum under the pretense of visiting a new medical institute.

When he realized the trap, Semmelweis tried to escape but was severely beaten by the guards. He was put in a straitjacket and confined to a dark cell. In a final, cruel twist of irony, the man who had spent his life trying to prevent infection died just two weeks later from gangrene caused by an infected wound on his hand—essentially, the same sepsis that had killed the mothers he tried to save.

It would be years before Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister would validate the germ theory of disease, proving Semmelweis right. Today, he is recognized as a pioneer of antiseptic procedures and epidemiology. However, his name also lives on in the "Semmelweis Reflex"—a metaphor for the reflex-like tendency of human judgment to reject new knowledge because it contradicts established norms, beliefs, or paradigms.