The Bullet, the Inventor, and the Dirty Hands: How Science and Ego Doomed a President

On the morning of July 2, 1881, President James A. Garfield was walking through the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C., preparing to leave for a college reunion. Out of the shadows stepped Charles J. Guiteau, a delusional lawyer and disappointed office-seeker who believed he was destined to be a diplomat. Guiteau fired two shots from a British Bulldog revolver. One grazed the President’s arm; the other lodged in his back, shattering a rib and burying itself deep within his abdomen.

What followed was one of the most tragic and frustrating episodes in American history—not because of the assassin’s aim, which historians agree was likely survivable, but because of the horrific medical malpractice that followed. The ensuing eighty-day struggle for the President's life would bring together the desperate prayers of a nation, the arrogance of the medical establishment, and the frantic ingenuity of America’s greatest inventor, Alexander Graham Bell.

Almost immediately after the shooting, the President was surrounded by doctors. In 1881, the germ theory of disease—pioneered by Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister—was gaining traction in Europe, but the stubborn American medical elite largely dismissed it as an invisible fairy tale. Leading the charge was Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss (his first name was actually "Doctor," a name given to him by his parents). Bliss, an ambitious and confident physician, took control of the scene and promptly inserted his unwashed finger into the President's bullet wound to probe for the slug. He was followed by other physicians who did the same, turning a sterile injury into a festering superhighway of infection.

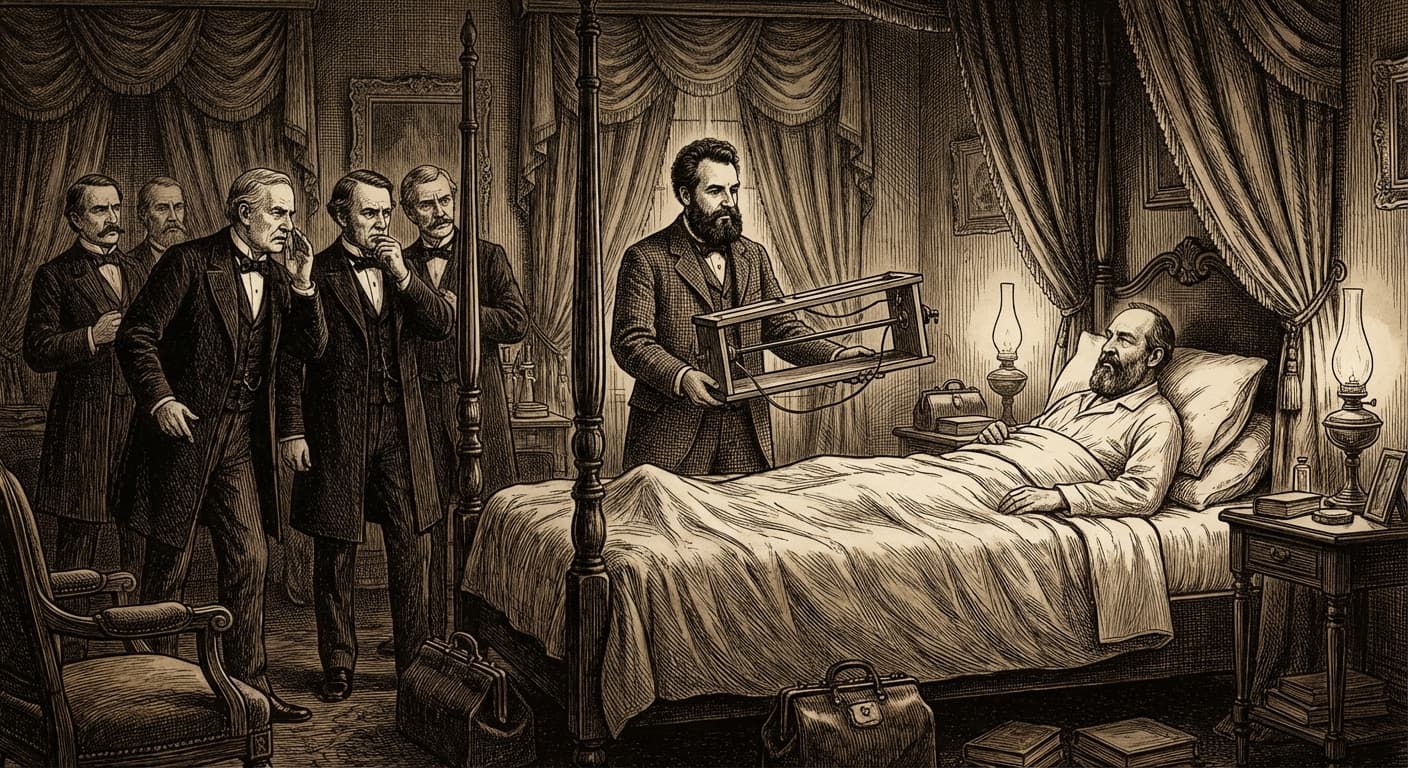

As the weeks dragged on and Garfield withered away in the stifling heat of the White House summer, the location of the bullet remained a mystery. The doctors, obsessed with extracting the lead, made repeated, agonizing incisions based on guesswork. Enter Alexander Graham Bell. The inventor of the telephone was devastated by the attack on the President and proposed a radical solution: a scientific device that could detect metal inside the human body without touching the skin. It was, effectively, the world's first metal detector.

Bell worked feverishly, creating an "induction balance" machine. He tested it on Civil War veterans who still carried bullets in their bodies, achieving successful results. With the nation holding its breath, Bell brought his apparatus to the White House to scan the dying President. The device hummed, signaling metal, but the signal was erratic and confusing. It seemed to indicate the bullet was in a place that made no anatomical sense. Bell returned to his lab, recalibrated, and tried again, but the results were the same. The doctors, trusting their own flawed intuition over Bell’s machine, dismissed the device and continued their invasive, septic probing in the wrong area.

Tragically, Bell’s invention had worked perfectly. The culprit for the confusing signals was not the machine, but a luxury innovation that Garfield was lying on: a coil-spring mattress. At the time, these metal mattresses were a rare novelty, and no one in the room—not Bell, and certainly not the doctors—realized that the steel springs beneath the President were interfering with the induction balance. Had they simply moved Garfield to a wooden cot, Bell likely would have pinpointed the bullet, allowing for a targeted extraction.

James A. Garfield died on September 19, 1881, not from the bullet itself, but from massive septicemia and a heart attack brought on by the infection introduced by his doctors. At his trial, the assassin Guiteau famously declared, "The doctors killed Garfield, I just shot him." While Guiteau was hanged for the crime, modern medical historians tend to agree with his assessment. The tragedy served as a grim wake-up call for American medicine, accelerating the acceptance of sterile antisepsis techniques that would eventually save countless lives, a legacy born from the dirty hands that lost a President.